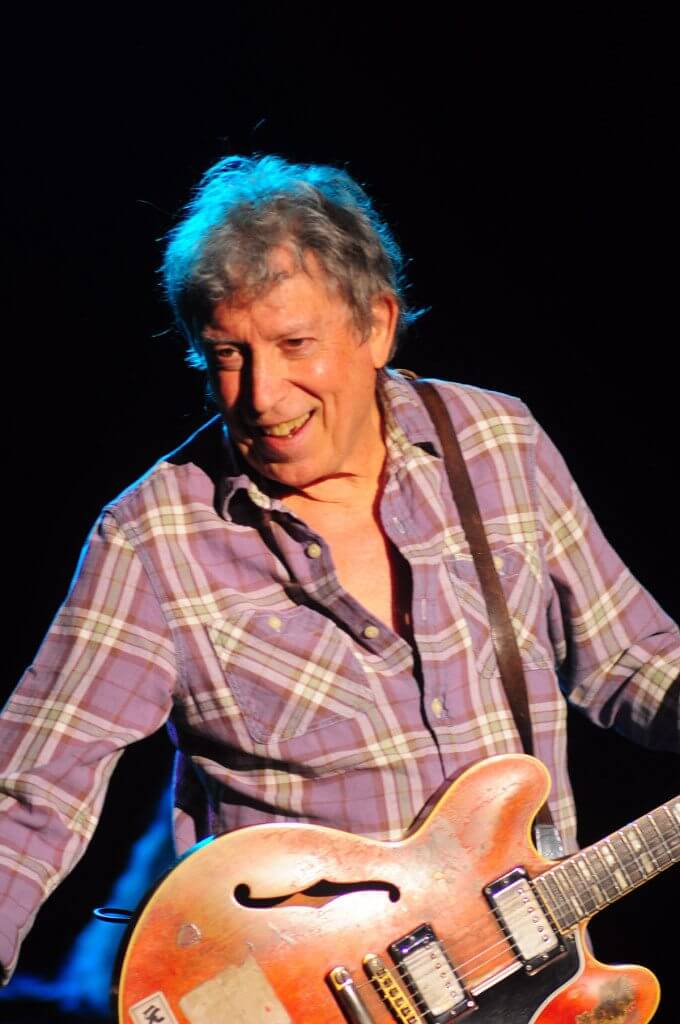

The Elvin Bishop Band and Pablo Cruise will celebrated Independence Day weekend with Red, White and Tahoe Blue.

in conjunction with the Crystal Bay Casino the bands will perform on the Incline Village Green at 7 p.m. Saturday, July 6.

the Incline Village Green is across the street from Lake Tahoe directly behind the Hyatt Regency Lake Tahoe Resort, Spa & Casino. Tickets are available online at www.crystalbaycasino.com, by phone at 775-833-6333 or at the Crystal Bay Casino.

Day of show tickets will be available at the Village Green at 5 p.m. All ages are welcome with specially priced $15 tickets for children 12 and under. Feel free to bring low-back lawn chairs, however, no coolers, food or beveragese. Food and beverage will be provided by sponsors Incline Spirits & Cigars, Big Water Grille and Brimms Catering. All net proceeds for this event will benefit Red, White & Tahoe Blue.

It didn’t take a British Invasion to learn the blues, Elvin Bishop did it by moving to Chicago and just being his amiable self.

Bishop famously met his future bandleader on his first day in town as a University of Chicago student. Paul Butterfield strummed a guitar and drank a quart of beer on the steps of his home when Bishop approached, drawn to the 12-bar riffs as if it was from the Pied Piper of Hyde Park. A native of the segregated South who mostly knew the music from Nashville radio station WLAC, Bishop was surprised and happy to meet a fellow blues enthusiast. Naturally, they hit it off. Bishop makes friends as fast as the Windy City’s wintertime “Hawk” blows off Lake Michigan, chilling its residents to the bone.

A couple of white kids getting Howlin’ Wolf’s rhythm section – drummer Sam Lay and bassist Jerome Arnold – to join their band isn’t so improbable when Bishop tells the story.

“Blues guys didn’t make that much money,” Bishop said. “It was a very fluid scene there. A lot of changing of personnel because if you made 10 or 11 bucks at one gig and somebody else offered you $12, there you go. That was the kind of money that was being paid. Butterfield, he got a job at Big John’s on the North Side of Chicago and it paid more than the South Side and West Side blues clubs. Not a whole lot more, but somewhat more.”

Butterfield was a harmonica savant, mastering the instrument in six months. The group picked up guitarist Mike Bloomfield and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band became popular playing music that more closely resembled that hometown’s sound than what the Brits had brought.

“I don’t think the British Invasion was even on the radar of the blues guys,” Bishop said. “It was not something they were conscious of or interested in.

“I think the real-deal blues guys and the British Invasion are a different phenomenon.

The Rolling Stones helped actually. The one decent thing they did in their lives was, in all of their interviews, they would pump up the blues guys.”

Mick Jagger sang praises while Bishop witnessed the life the bluesmen were singing about.

“I met Magic Sam when I was just a fan at about 18, maybe,” Bishop said. “He was playing at some big dance. I went there and I got kicked out of the place twice for being underage and I finally went around back and I got into the dressing room and Magic Sam let me stay and we became friends.

“He was as big as stars went in those days. He wasn’t like being Mick Jagger or something. He was well respected by the musicians and he was well liked by the people. Those guys, they were stars in that respect, but they were also just members of the community.”

Bishop also befriended Otis Rush, who had a demeanor that often kept many away.

“He was a different dude but he was really nice to me,” Bishop said. “I used to go over to his house and he would sit down and give me lessons or show me stuff. I’d go over there and he was real cool with it. First thing, he would go over to the kitchen cabinet and get this bottle of Old Grand-Dad and pour us both a shot, and we’d down the shot and then we’d sit down and go over some licks. He was just a cool guy.”

Although a country blues icon once stayed at his house, Bishop didn’t get any lessons from Mississippi Fred McDowell.

“I did from his records later but I wasn’t good enough at the time to catch any,” Bishop said. “I was just happy to be around him, talking to him like that.”

Bishop’s most influential mentor was Little Smokey Smothers, who played guitar with Butterfield before Bishop joined the band. Their bond was unusual, considering the times.

“This was right on the edge of two cultures,” Bishop said. “The civil rights thing hadn’t happened yet and the divide down South where I was from was so drastic and so hard core that when you finally got a chance to associate with people of the other race on equal terms, only certain people could handle it well.

“People never got used to certain people, (some) were just positively were bad at it. Smokey Smothers was just one of those guys that we just fell together like a couple of brothers. Just wasn’t any problem.”

In the late 1960s music promoter Bill Graham did what the British Invasion could not: Turn Americans onto the blues. He put blues artists like B.B. King and Albert King on showbills at the Fillmore West in San Francisco and Fillmore East in New York with rock bands the Jefferson Airplane and Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company and Santana.

“Graham was the one who really caused it to cross over big time,” Bishop said. “He started using blues acts at the Fillmores and all of the other kind of hippie venues throughout the country followed Graham’s lead.”

Bishop in 1968 decided to move to Northern California, citing more gigs and “the lack of the Hawk.”

But his Chicago years were invaluable to someone who at 70 years old is now himself a blues statesman.

“It was a really lucky time to be there,” he said.