Editor’s note: Billy Boy Arnold was in Tahoe onstage Jan. 3 as part of Mark Hummels Blues Harmonica Blowout.

Seventy nine year-old Chicago blues artist Billy Boy Arnold can speak of the authenticity of the blues. He also at an early age learned about charlatanism.

When he was 12, Arnold befriended and took lessons from John Lee Curtis “Sonny Boy” Williamson before the first popular harmonica recording artist was murdered at the age of 34. Arnold later confronted Alex “Rice” Miller, who assumed the stage name Sonny Boy Williamson after the first Sonny Boy was killed.

“I was 15 and he was sitting there with Elmore James,” Arnold told Tahoe Onstage. “I said, ‘You’re not Sonny Boy. I know Sonny Boy.’ He just said, ‘You want my job. You want my job.”

Witnessing the encounter was Little Johnny Jones, who was playing in James’ band and happened to be at the original Sonny Boy’s Chicago home when Arnold and a friend knocked on the door.

“I was 12 years old and I asked him how he went about playing harmonica,” Arnold said. “He got me interested in his music when I was 11 years old. Six months later I was 12 and went to his house. I found out he lived only two blocks away from my uncle’s store on 31st Street. I found this out from a musician I met on the street.

“I didn’t know what he looked like. A well-dressed man came to the door. I said, ‘We’re here to see Sonny Boy.’ He said, ‘This is Sonny Boy.’ ‘We’re here to hear you play harmonica.’ He said, ‘Come on up, I’m proud to have you all.’

“I asked how you play ‘wa wa wa.’ Now they call in bending the notes but back in the day they called it choking. I was already inspired when I first heard his records. I didn’t necessarily want to be a professional, I just wanted to know if I could do that. I had two lessons before his untimely death.”

Arnold soon was a professional, but it was not at all lucrative.

“I was playing in band in 1953,” he said. “We weren’t making any money at all. In fact, it was quite a joke: $5 a night per man.”

Arnold performed on street corners with Ellas McDaniel, better known as Bo Diddley. He also played harp on Diddley’s first recording session, which included the popular song “I’m A Man.”

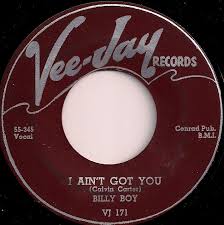

“My goal from the day I heard Sonny Boy’s music was that I wanted to be a star in the same right that Sonny Boy Williamson was. I made my first record at 17. After me and Bo Diddley parted company, a few months after he made his hit, I want to Vee-Jay records and recorded ‘I Ain’t Got You’ (Later recorded by Jimmy Reed, the Yardbirds and Aerosmith) and ‘I Wish You Would.’ It was a fun time to me.”

In 1955 Arnold was included in the first blues session that included electric bass, which a couple years later became a standard component in a blues band.

Occasionally, there would be white faces in the audiences, including those of Charlie Musselwhite, Paul Butterfield and Elvin Bishop.

“Those were the first white audiences we inspired as musicians to be blues players,” Arnold said.

Arnold said after white people became interested in blues, blacks would say the blues must be all right. And, conversely, whites would say because blacks enjoyed it, it must be all right.

“The blues has always been all right,” he laughed.

Arnold also saw the emergence of rock and roll.

“Rock and roll started in the 1920s with the black piano players,” he said. “Anything that you hear guys playing that they call rock and roll, it ain’t nothing but boogie woogie blues piano playing. Jimmy Reed did the same thing with the guitar, and Chuck Berry played the same thing on the guitar. Rock and roll sounds like black music. Boogie woogie blues. Rock and roll is another name for it, but it’s nothing but blues.

“Four people are responsible for giving white people around the world, getting them the blues: Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry and Little Richard. Whites couldn’t hear real black music because of discrimination. Then there was the British Invasion. The British liked the blues and that was alright with me. Everybody would like the music because the blues is a special type of music. It’s a feeling, an expression.”

While Arnold has often been a band leader, he’s also shared the stage with blues legends such as Otis Rush, Otis Spann and Earl Hooker.

“Earl Hooker was one of the greatest guitar players I ever saw onstage, Arnold said. “Amongst the musicians he was appreciated. He played with original Sonny Boy Williamson at 16 and with Muddy Waters but blues is about singing. Classical music is instrumental music. Jazz is about instrumental music. Blues is about singing and telling a story. Earl didn’t sing very much, that’s why he didn’t make it big as a recording artist but everybody knew all over the country that he was the greatest guitar player you ever saw on stage.”

And the greatest harmonica players?

Arnold says Little Walter Jacobs and, of course, the original Sonny Boy Williamson.

“There was no one on harmonica on records at the time; he was the guy who started it,” Arnold said. “He’s the man who put the harmonica on the map. All the guys now who are playing all over the world, either directly or indirectly, are going off of John Lee Sonny Boy Williamson’s music.”

Mark Hummel’s Blues Harmonica Blowout: Bluebird Records Tribute

Artists: Mark Hummel, Billy Boy Arnold, Elvin Bishop, Rick Estrin, Little Charlie Baty, Steve Guyger, Rich Yescalis, Bob Welsh, June Core and R.W. Grigsby

When: 7:30 p.m. Saturday, Jan. 3

Where: Harrah’s Lake Tahoe South Shore Room

Tickets: $49.75