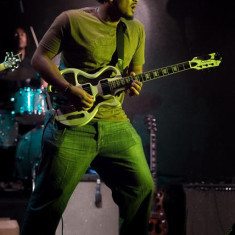

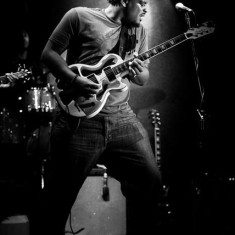

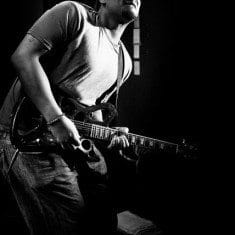

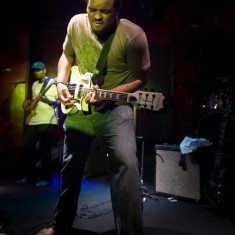

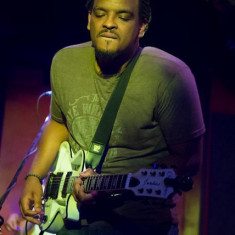

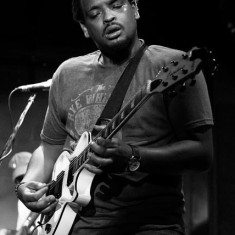

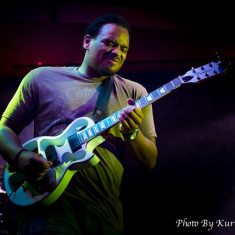

Editor’s Note: Jarekus Singleton had never been to Nevada until he performed May 25 in the Crystal Bay Casino’s Red Room. After a scintillating show, there is no question that he will be invited back, and soon, we hope. Just signed to Alligator Records, Singleton and his tight band — cousin Ben Sterling, bass, longtime friend John “Junior” Blackmon, drums, and uncle Tony Shearry, rhythm guitar — played most of the tunes from the new album, “Refuse to Lose,” along with tracks from his first record and some blues standards played in unique and brilliant arrangements. The 29-year-old from Jackson, Miss., is leading the music’s genre in a new direction, with modern-day funk and even hip-hop styling. Yes, the former basketball point guard is a blues’ vanguard.

“Refuse to Lose” is more than an album title to Jarekus Singleton, who has just released his debut CD with Alligator Records. PURCHASE It is a mind-set.

Before he was a shooting blues star, the 6-foot-3 Singleton was a basketball sensation. The NAIA 2006-07 Player of the Year led the nation’s colleges in scoring, and he was fifth in assists.

“I always had to prove who I was because I wasn’t the one who jumped the highest or ran the fastest,” Singleton told Tahoe Onstage. “I never played a game on some AAU teams. But once I got a chance to play, I was always the best player on the team. I just had to prove that I belonged. That’s where “Refuse to Lose” comes from.”

The NBA did not call upon Singleton after he finished William Carey University, a small Mississippi Christian college. Undaunted, he moved to Lebanon where he played professionally. But when a severe ankle injury caused his cartilage to resemble the rubber strings inside a golf ball, his hoops career was over.

Singleton moved back home where he was in a cast for 18 weeks.

“I was at ground zero,” Singleton said. “My mama had to help me take baths. She was instrumental in getting me back on my feet, literally.”

At the age of 29, Singleton has arthritis, which flares up when the weather changes. He has to exercise and to stay off his feet when he can. Living with the bad ankle is a constant chore. However, the devout Christian marches forward without a mental limp.

“I just thank God at a second chance at following my dreams. Whatever comes with it, I am willing to take it with no complaints,” he said.

The International Blues Challenge is a music version of the NCAA Basketball Tournament. Each competitor is confident of victory. There is only one winner, and there are scores of losers. The determined Singleton relentlessly returned to the IBC in Memphis. He never won it.

“I just got pissed off every time,” Singleton said. “Any time you lose, it’s devastating. I looked for reasons to go back and fix some things. I am really a soul-searching type of guy. Each year I walked into the Orpheum (Theatre, the site of the IBC finals). I wanted to smell it. I wanted to taste the air. I wanted to feel how it felt to be in there. I never knew how it felt to be on that stage and every year that was my motivation to come back.

“I used it as a platform, as well; like playing in the NCAA Tournament or if you play football in a bowl game. That’s where people get a chance to see you on a national level.”

The scout in the stands wasn’t a cigar-chomping Red Auerbach from basketball’s most winning franchise. It was Bruce Iglauer, the founder and president of Alligator Records, the Chicago label that has been at the forefront of the blues for more than four decades.

Iglauer recognized Singleton’s potential but said his singing and songwriting needed further development. The Alligator president said was impressed with Singleton’s character. He kept an eye on the young gunslinger from Clinton, Miss. for another year, then signed him after the following IBC.

Singleton, who has a penchant for metaphors, didn’t win the NCAA tourney, but he inked an NBA contract.

In the past decade, Alligator signed veteran blues artists Tommy Castro, Rick Estrin, Marcia Ball and R&B’s J.J. Grey and jam-rocker Anders Osborne. It had been several years since Iglauer signed a young African-American bluesman as he did with artists like Son Seals, a player who had vast knowledge of where the music originated. That wasn’t the case with Singleton, who said he was a rapper before he picked up guitar.

“Jarekus had never heard Gatemouth Brown because who would have told him about Gatemouth Brown?” Iglauer said. “So in a very strange reversal of normal roles, I have been teaching him more about the blues tradition because he had had really no way to learn it.

“He was learning a lot from records but I remember him asking, ‘Is that a Jimmy Reed record?’ I said, ‘No, that’s a Little Walter record.’ It was strange to me he didn’t know, but if you think about his background, that makes sense. He didn’t grow up surrounded by blues like older blues musicians did.”

Singleton said he was encouraged as a boy by his mother and grandmother to write poetry, especially at church.

“I love Bruce because he was very receptive to the approach I was doing,” Singleton said. “He said, ‘I can teach you to write like everybody else but if I do that we can’t move this genre forward. He’s been nurturing my talent; he never tried to change who I was.

“I’ve learned how to write more efficiently and I’ve learned how to look at it from a listener’s perspective. Can you listen to it and a picture be painted for you without you having to see the video on TV? That’s how Bruce helped me with my writing. He made me tell the story a little better.”

Earlier, Singleton was mentored by the late Michael Burks, the great Albert King protégé. He said he approached Burks before a show in the 930 Blues Café in Jackson, Miss.

“The guy sat there and talked to me for an hour before he even knew who I was,” Singleton said. “He was the nicest guy in America.”

Months later, Burks surprised Singleton with a phone call.

“From that day forward he would just call me and encourage me and give me pointers about what to do as a guitar player and as a businessman, and about writing your own songs, doing your own material. I marveled as his success as a guitarist and I really liked his style.”

Like Burks, Singleton has an aggressive guitar delivery. His vocal tone sounds like a gruff Robert Cray. The songwriting is clever and unique. There are rhymes within rhymes, as in a hip-hop song.

“Refuse to Lose,” which has 12 Singleton originals, was released this month. His studio band, which includes a cousin and a childhood friend, also is the touring group.

Iglauer is almost giddy about the potential of his new artist, saying he could be a bluesman of a generation.

Singleton takes such praise in stride, consistent in his steadfast determination.

“I don’t feel any pressure,” he said. “I feel a responsibility to move this genre forward. I can’t do what Stevie did. I can’t do what Muddy did. I can’t do what Charlie Patton did. I can’t do what B.B. King did, or Freddie or Albert. Those guys were the best at what they did. I am very much inspired by what they did. In the foundation of what I am doing now, I just have to be the best Jarekus that I can be.

“I’ll let people tug of war with what they think. I am more about the significance of everything that I am doing. When I am writing a song and somebody says to me in an email or Facebook message, ‘Jarekus I can relate to what you are doing. My car was stolen or I was cut from my job, I had to start back over. I had surgery.’ Those are the things that help me. That’s where I realize why God put me on this earth was to use the gift he gave me to inspire other people to get through whatever they are going through in their personal lives.”

Is it possible an ankle injury was a godsend? Maybe. The NBA only lasts a limited amount of time.

“I am in love with what I am doing and I’m obsessive with what I’m doing,” Singleton said. “I don’t want to have an offseason. To me this is not a career. This is a way of life.”