Denny Laine Facebook image

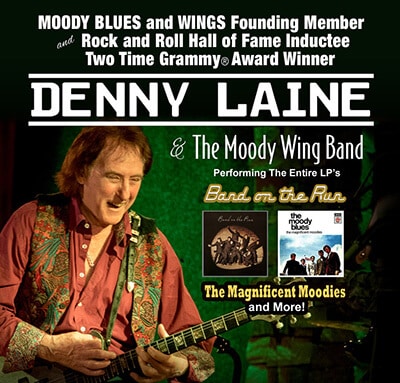

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member Denny Laine was an original member of the Moody Blues and was with Paul McCartney and Wings during its entire 10-year run. Laine has released several solo albums and been with many other bands, including Ginger Baker’s Air Force, Balls and the Electric String Band. He played with his Moody Wings Band at the Crystal Bay Casino on July 27. The last time he performed at Lake Tahoe, he was with the supergroup World Classic Rockers. He cowrote with McCartney the 1977 Scottish folk song “Mull of Kintyre.” On Saturday, Laine and the Moody Wings Band will perform songs from the Moody Blues breakout album, “The Magnificent Moodies,” and Wings’ “Band on the Run.”

Laine spoke with Tahoe Onstage recently:

Was “Go Now” the first big hit for the Moody Blues?

Yeah. It happened during the Chuck Berry tour and it went to No. 1. That’s what happens when you play live. A lot of people go out and buy your records.

I love blues. Do you still play that Sonny Boy (II) Williamson song “Bye Bye Bird” from “The “Magnificent Moodies?”

Yeah, I still do. My roots are in jazz and blues. That’s why the Moody Blues are called the Moody Blues. That’s why I like to do that first album because it relates to that style more.

It’s odd that it took the Brits to introduce us to our own music.

You can blame the American Forces Network in Germany for the British Invasion because we were very influenced by the music they were listening to. We heard that in England. A lot of it was early R&B and blues as well.

When did you meet Paul McCartney?

I first met him with my band, the Diplomats. We opened for the Beatles in a ballroom in Birmingham. Then I met him down in London when I was with the Moody Blues and we became friends straight away. That led to us signing with (manager) Brian Epstein.

Those were the shows with all the screaming girls.

We had some screaming, too. But you could hear us. You couldn’t hear them with all the screaming going on.

Then you played with the Electric String Band.

Yeah. That was my first solo venture. I did about a year of that, and then I did a show with Jimi Hendrix where Paul and John were in the audience. I think Paul seeing me do that inspired him to later on give me a call (for Wings). This was after the Ginger Baker stint that I did.

I understand before the making of “Band on the Run” a couple of guys dropped out and Wings became a trio (with Paul and Linda McCartney). You were in Lagos, Nigeria and Paul and Linda were robbed.

We all had separate houses on these country estates and they walked from their house to our house. They shouldn’t have done it. They were warned and, yeah, they got robbed and they took everything they had.

Including the demos and music?

Yeah. I didn’t know the two other guys (Denny Deiwell and Henry McCullough) weren’t coming until the last minute. But we just went about it on our own. The studio had been rented. Paul played drums, I played guitar and we went through as many songs as we could remember the arrangements. We used those as a basic track and we worked from there. You just do what you’ve got to do, and it had a really good feel. To tell you the truth, it was a lot easier working with just the two of us because with a band there are more people to deal with.

So, you had a good rapport with McCartney?

Oh yeah. We always had good communication because we were brought up on the same stuff and we knew each other. We would always come out with something, a more or less finished song. They would do that with the Beatles and we would do that with the Moodys. We would come out with something finished. You got so used to, in the early days, doing more than one song. You had a three-hour session. That’s the way it worked, especially if you were working with unions. So, you would go in there and probably come out with three songs. But with Wings and earlier with the Beatles, we had open studio time, so we had more freedom to create in the studio rather than plow through the studio.

Did you do sessions with the Beatles?

No. I went to one of them. They were doing “Fool on the Hill.” Paul invited me, and we went upstairs to see this band that was doing an audition. It turned out to be Pink Floyd. They were getting a deal at the time, yeah.

You wrote “Japanese Tears” after Paul was arrested for possession of marijuana. You must have been with him when that happened. Was it at the airport?

I got back to the hotel and I didn’t even believe it. I thought the roadie guy was winding me up when he said Paul had been busted at the airport. The band all came though the customs area together. Then I was told to carry on and get in the car and back to the hotel. Then I heard later that they’d looked in his bag and found something. It was a big deal, but it could have been worse. It cost a great deal of money to get out of it. They made an example of him, really.

You played “I’m a Man of Constant Sorrow” in 1970 when you were with Ginger Baker’s Air Force. Thirty years later, that song in the movie “Oh Brother Where Art Thou?” inspired a generation of bluegrass players in the United States.

These are all traditional American folk songs. In England, they called it skiffle, what we called bluegrass. I’m a huge fan of bluegrass. I love the version that they did. It was more like the original version anyway. My version was more taken from Bob Dylan’s version. … We put it out as a single. It was a good period for me. I love blues and I love folk music, and that influence came into Wings a lot.

Was “Mull of Kintyre” your biggest hit?

Yeah, and again, that was a folk song, with haunting drums and bagpipes in the background. That’s exactly what we were influenced by: Scottish folk. That became the biggest thing in England, for some reason. It was Paul’s attempt to write a Scottish song. He was a little bit worried about it because he didn’t know what the reaction would be, but once they put the bagpipes on it, it sounded so authentic. I helped him write a lot of the lyrics, but he had the chorus. That just showed where our influences were. We were very much based in Irish, Scottish, English folk music as kids.