Photo by Lola Reynaerts

Editor’s note: Chicago bluesman Jimmy Johnson died on Jan. 31, 2022 at the age of 93. The following feature story first published in 2020 details Johnson’s amazing career.

Poetic justice came to Jimmy Johnson during his first trip to Japan.

A soulful tenor singer and tasteful guitar and keyboard player, Johnson was a member of Jimmy Dawkins’ blues band in 1975 when it landed in Tokyo.

“They had signs and cartoon cutouts of us at the airport,” Johnson said of the crowd that greeted the musicians. “I thought I was with The Beatles. They were really into the blues in Japan.”

There is irony in Johnson’s reference to The Beatles, which was the most popular band from The British Invasion into the United States in the early 1960s. The British groups played their versions of American blues and were far more popular in the foreign land than the authentic performers in America.

Johnson’s hometown Chicago was the hub of electric guitar-driven blues and many of his peers were bitter about being underappreciated.

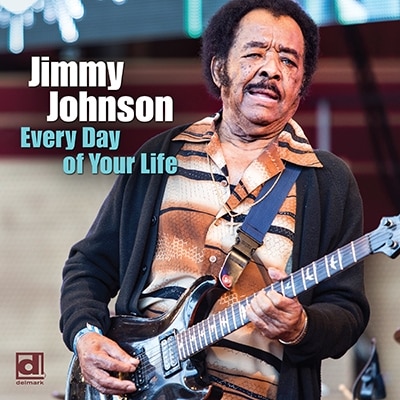

“I see quite a few of the guys, they were very resentful. You get a foreigner and you’ll play their record on the radio but you won’t play your own people’s record,” said Johnson, who on Jan. 17 — at the age of 91 — released a superb album on the Delmark Records label, “Every Day of Your Life.”

“Some of the guys, they felt like some of the British groups did the same thing that they did and they get way ahead of you. That’s kind of frustrating but I go through life and I don’t let nothing frustrate me. That’s how I lived to get this this old. I look at it like this: It is what it is. And one more thing, why cry about what you don’t have? Be thankful for what you’ve got.”

It’s unlikely the nonagenarian Johnson will perform again in Japan or Lake Tahoe. He stopped touring in 2016 and has only been playing at Chicago venues.

Johnson played at Tahoe in 2009. He remembers playing in cold, 45-degree conditions, at Harveys Outdoor Arena, along with blues stars Lonnie Brooks, Eddie “The Chief” Clearwater and gospel singer Mavis Staples. It was the only time in the 19-year history of the Lake Tahoe Summer Concert Series that it rained during the entire show.

“I was in Tahoe just the one time and it was a bad experience but what was so hip about it was when I got off the plane in Reno, I had a personal limo to bring me up there and bring me back,” he said. “That was real gratifying. I am somebody. I got a personal limousine just for me.”

Johnson performed recently with fellow Chicago great Buddy Guy, who is 83 and continues to tour.

“I told Buddy, ‘You’re too old. Why do you keep running up and down this road?’ He said, ‘I need the money.’ I said, ‘No, you don’t.’ ”

“Now that I have this record, they will probably start bugging me to go out on the road,” Johnson said. “But it will be very tough to get me on a plane to go anywhere. I ain’t going to be like Buddy and say I have to, because I don’t have to.”

So, fans of Johnson who don’t live in Chicago will need to be content by listening to the album, “Every Day of Your Life.” Johnson feels it’s one of his best three, along with 1983’s “Bar Room Preacher” and 1994’s “I’m a Jockey.”

“Every Day of Your Life” was recorded in two days with two different bands that included some of Chicago’s finest musicians. The title track and “My Ring,” which is played to a reggae beat, had been released previously on a record label that has closed.

“I wasn’t happy with them (on the earlier records) but this time it’s better quality and what really helps is the groove,” he said. This was a fire band.”

Johnson’s passionate vocals are as strong as they’ve always been. In contrast to many Chicago blues guitar players, Johnson is not a string bender or slide player. He plays with low action and a soft touch. His delivery is what makes his music so honest and heartfelt.

As he did twice on “Bar Room Preacher,” Johnson covered Fenton Robinson. The song is “Somebody Loan Me a Dime,” which became a hit for rock and roll singer Boz Skaggs.

“I knew (Fenton) for many moons,” Johnson said of his friend who died in 1997. “Fenton was a very good singer and very good a writer. I put him above the crowd but they didn’t push him up there, but I put him up there in my book.”

Six of the songs on the new album were written by Johnson, whose publishing and birth name is James Thompson.

The second eldest of 10 brothers and sisters, James “Jimmy Johnson” Thompson was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi. From the time he was 8, Johnson worked all day on a farm, picking cotton and tending to livestock.

He was childhood friends with Matt “Guitar” Murphy, who is best known for playing in the band and movie “The Blues Brothers.”

“We grew up in the same town together, playing baseball, shooting marbles. Matt had a guitar and sometimes he let me take it home with me, but I didn’t really know how to play,” Johnson said.

At the age of 16, Johnson moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he lived three years working various jobs, including as a bellhop earning $14 a week at the Peabody Hotel and digging holes for a man named JD Fox.

“Up to this day, he still owes me $8,” Johnson said. “That was back in the ‘40s. So if you ever see JD Fox’s company, let me know because I’m going to sue them for my money.”

Johnson moved to Chicago to find better work and to escape the Jim Crow laws that oppressed black people in Tennessee, Mississippi and the rest of the South for almost 100 years after the end of the Civil War.

“I moved up to Chicago with my uncle and I was very fortunate because by the third day I had a real good job. Within a year’s time I was a Class A combination welder. I was making a lot of money.”

Johnson was generous with his cash, sending funds to family members so they could move North, too. He also bought guitar strings for a teenaged neighbor who had been playing with just a single string on his instrument.

“Magic Sam moved next door to me and he got to be a star at 15. I said, ‘Wow, I probably can do that.’ Then I got a guitar. I was 29 years old.”

Johnson’s brothers Syl (seven years younger) and Mac later the moved to Chicago. Mac became best friends with Magic Sam and is credited with coming up with the nickname for Samuel “Magic Sam” Maghett. “He was closer to Sam than he was to me. He played bass for him for 20 years.”

Syl, who continues to perform as an R&B singer, was an accomplished guitarist who did studio work with Jimmy Reed, Eddie Boyd and Junior Wells.

“When he got to be a star, he put his guitar down,” Johnson said.

Early in his career, Syl made a record. The record company mistakenly wrote the name Johnson instead of Thompson.

“He couldn’t afford to have more labels made so he just said, ‘I’ll live with Johnson.’ That was a very good record. It made a lot of noise. I could get more gigs because I was Syl’s brother, so I went as Johnson, too. If I get a gig and say my name is James Thompson, they paid me $200. If I say I’m Jimmy Johnson, I’m Syl’s brother, I get $500. So that’s why I changed my name. By him being big, that puts me up a notch, too.”

Jimmy Johnson’s professional music career began playing gospel in churches for the groups United 5 and Golden Jubilaires, which had a teenage singer named Otis Clay.

Johnson played briefly in a blues band, The Aces, a group led by Louis and Dave Myers and at times featured Little Walter and Junior Wells. But Johnson, who was a more accomplished singer than he was a guitar player, found more work in R&B.

In the 1960s, Johnson played in R&B bands, including the Lucky Hearts. “We had two guitarists, which was unheard of back then, except for The Beatles,” Johnson said. “I played every night of the week, sometimes two gigs a night. There was a club on every corner.”

Johnson’s guitar skills improved under the tutelage of jazz teacher and studio player Reggie Boyd, who also mentored Syl, Fenton Robinson, Otis Rush, Louis Meyers, Howlin’ Wolf and Dave Specter.

Johnson transitioned to the blues in the mid-1970s when he received an offer to play with Jimmy “Fast Fingers” Dawkins, who needed a reliable bandmate to tour with in Japan.

“You need someone with quality, and you need somebody that you can depend on to show up and to hit the stage. That’s me up and down.”

While poetic justice was served to Johnson, Dawkins and Otis Rush when they played to appreciative audiences in Japan, sushi and sashimi was not, at least for Johnson.

“That’s the raw fish?” Johnson said. “No, I grew up in Mississippi. A lot of people say fish is not a meat but it is. Fish is meat and we don’t eat raw meat. Here’s what my grandmother would tell you: You have no idea if that animal sick or not. If you cook that meat, you kill whatever germ was in it. That’s what I grew up with.

“That’s one of the problems I had in France, they don’t hardly ever want to cook anything done. They say you’ll cook the taste out of the meat. Well, just cook the taste out of it for me.”

Johnson missed out on authentic Japanese food but he savors his three tours in Japan in 1975, 1990 and 1999.

Performances July 20-29 at Hibiya Yagai Ongakudo backing Otis Rush was made into an album, “Otis Rush – So Many Roads.” Rush and Johnson played guitar, Sylvester Boines bass and Tyrone Century drums.

“When I played in Japan, I really enjoyed it because the people were so much into the music,” Johnson said. “It was probably the most enthusiastic audience I’ve played for in my life.”

Johnson was amazed at the culture and the quietness of its cities. Motorists in noisy Chicago get around using three primary instruments — the accelerator, brake pedal and horn.

“The (Japanese) people don’t throw garbage out on the street,” he said. ”Ever been to Switzerland? It’s the same way. It’s the mentality of the people. In Japan, you won’t even hear people blowing their car horn. You won’t see a car that’s bent up. You don’t have people getting loud and arguing. It’s one of the most peaceful places I’ve ever been.”

After he returned home, Johnson became a regular player throughout the city, including Buddy Guy’s famed Checkerboard Lounge in 1976. A professional for nearly a quarter of a century, Johnson laughed at a news article calling him an overnight success.

“I don’t know what you’d call it,” he said. “I’m a normal guy. But I was a big success in Europe first. I am well known in Chicago but I ain’t no big success.”

He also scoffed at the notion of different styles in Chicago’s South Side and West Side. His neighbor Magic Sam’s greatest album was called “West Side Soul.”

“I played on South Side then there was a time I played on the West Side. There wasn’t no difference. People saying that’s West Side, that’s South Side. That’s just something they made up. It’s Jimmy Johnson blues, Freddie King blues, B.B. King blues, Albert King blues – they’ve got nothing to do with where you’re from.”

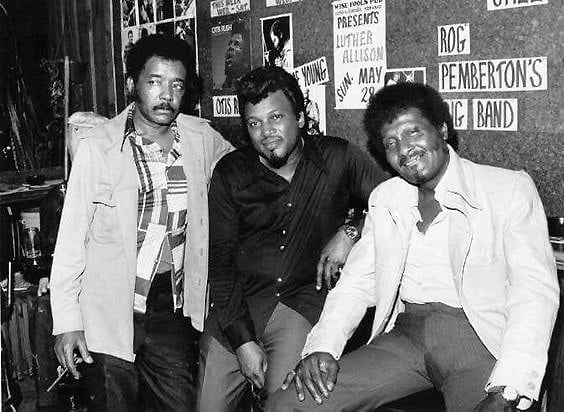

Erik Lindahl photograph

In actuality, the players were originally from the South, and most were from Mississippi, including Rush, Dawkins, Robinson, Magic Sam, Guitar Murphy, Eddie “The Chief” Clearwater, B.B. King and Albert King. Louisiana produced Little Walter, Buddy Guy and Lonnie Brooks, and Freddie King and Albert Collins were from Texas.

The established players were known to look out for the new ones. Johnson has his guitar stolen during a break at hot afternoon summertime show. The back door was barred, but that didn’t prevent the theft.

“The joint was loaded but nobody saw what happened,” Johnson said. “Somebody must have passed it through the bars. Freddie King had an extra Les Paul and he lived around the corner. He walked home and loaned it for me. A week later, I had made enough to buy a (Gibson) 335.”

After James Brown’s August 1968 release of “Say It Loud – I’m Black and I’m Proud,” opportunities dwindled.

“That wiped all the black bands out of the white clubs,” Johnson said.

While there’s no Jim Crow in Chicago, segregation and racism has continually increased and, Johnson said, “it probably ain’t going to get no better. … I don’t mind if you print it because I live in a prejudiced world.”

Johnson recently cleared up voice issues after being diagnosed and treated with water pills. He’s stopped playing a heavy Gibson guitar and now carries a lighter Paul Reed Smith. An hourlong conversation demonstrated that at age 91 Johnson remains as mentally sharp as one of his piercing guitar notes. He’s been using email and the internet to arrange his shows since the 1990s.

“You’ve heard the expression, ‘If you don’t use it, you’ll lose it?’ Dementia or Alzheimer’s, whatever you call it, sometimes it’s hereditary but sometimes it depends on you. You should never stop your brain from operating. Most people my age are afraid of a computer. But if you don’t challenge your brain, in my opinion, it’s going to die out.”

Johnson said he disdains sitting around the house, watching television. He has a Sunday jazz residency with Leo Charles — a music professor — at Lagunitas Brewing Company, performs around the city with his own band, plays solo piano shows and has an upcoming gig with his brother Syl.

“I listen to everything except rap,” he said. “I even listen to country sometimes. Mostly, I listen to all kinds of music. Jazz. I like soft rock. I listen to what they call R&B soul music.

“I can’t say every day is great. Some days are a little better than others. Well, at my age, what do you expect? It comes with the territory. But I play and practice and sing to keep my voice in shape.”

For someone who only started playing guitar in earnest at the age of 29 and had his first solo record at 50, Johnson has had an enduring career that places him in the pantheon of all-time great Chicago bluesmen. In 2016, he was enshrined into the Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame in Memphis. At the 2019 Chicago Blues Fest, Chicago Major Laurie Lightfoot officially declared it to be Jimmy Johnson Day. And his new album, ”Everyday of Your Life,” to borrow one of his expressions, is making a lot of noise.

“I got more press on this record than I did on the rest of them and some of those records were really good,” he said.

Poetic justice, indeed.

— Tim Parsons

Album review: Johnson back in fine for with ‘Every Day of Your Life.”