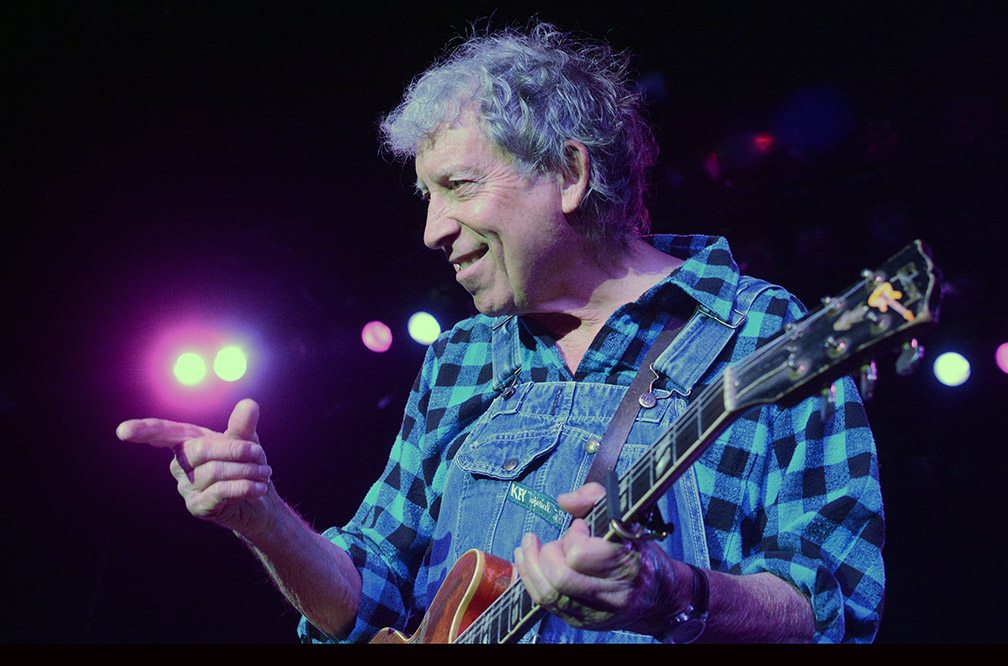

Tim Parsons/Tahoe Onstage

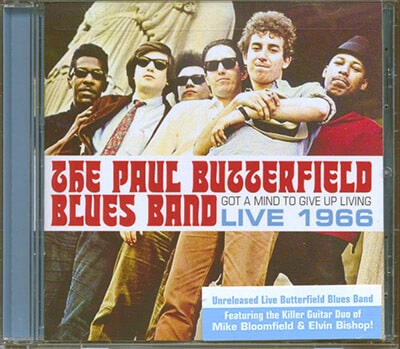

Elvin Bishop’s five-year run with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band is well documented, but it’s a rare treat to hear stories of his time in Chicago before he joined the future Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band.

Ostensibly, Bishop moved to the South Side of Chicago to get a college education, but within a week, he dove into his favorite subject. And he didn’t learn blues in a classroom or by theory.

“I took the more direct route,” he said. “Just go to the ghetto. They had plenty of blues there.”

The first band he witnessed included Muddy Waters, Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, James Cotton and Pat Hare.

Book smart enough to earn an academic scholarship to the prestigious University of Chicago, Bishop’s common sense and amiability were the characteristics that allowed the white country boy from Oklahoma to successfully integrate into black society.

“People don’t realize what a huge scene the blues was there. There were, I swear, more than 100 blues clubs in Chicago if you count the West Side and the South Side. … At that time, blues was the No. 1 music of the black culture. There were millions of black people there, so they could support a lot of clubs. It’s like rap is now or hip-hop. It was that popular.

“I always had sense enough to go with a group of black guys, you know, and not leave no $100 bill — as if I’d ever seen one — hanging out of my back pocket.”

“On the West Side, the people were poorer and it was a little bit more low down, you know. And a lot of the clubs over there, you notice it. Like Magic Sam and those guys had smaller bands. They wouldn’t normally have horns and stuff because the economics weren’t there for it.

“I played with a lot of little groups around Hyde Park where the university is. The first ghetto blues gig I got was with this guy J.T. Brown. He was like one of these old honkin’ sax players from the ’40s He played on a lot of Elmore James records.

“J.T. Brown and Hound Dog (Taylor) played in little joints. The really didn’t even have a stage. You set up on the on the floor in the rear of the club. You’re right there, with the people who were dancing and everything. It was a low-level gig but it was a real-deal thing and I really enjoyed it.”

Stew’s brewing: Veggies calling from the garden

Bishop recalled his early Chicago days in a telephone interview that was interrupted when he went to his garden at his home in Northern California. He needed to pick some vegetables for a beef stew.

“Keep your finger in the page there and then I’ll get right back to you,” Bishop said.

When he called back, Bishop said that XM satellite radio stirred some more memories. A new song by his friend Paul Thorn is getting a lot of air play, “Jesus Gonna Make Up My Dying Bed,” which features fingerpicking guitar from Canadian artist Colin Linden.

“You can’t listen to that without thinking of Mississippi Fred McDowell,” Bishop said. “It’s the same tuning. That Canadian guy’s been listening to that record, “Keep Your Lamp Trimmed and Burning.”

As a student, Bishop said he lived in house full of folk musicians.

“Blues was considered a small department of folk music,” he said. “And every folk festival would have token blues artist on it. Maybe Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee or someone like that. They would get Fred McDowell to play at the Chicago Folk Festival. And when he came up, he would stay at my house in Chicago.”

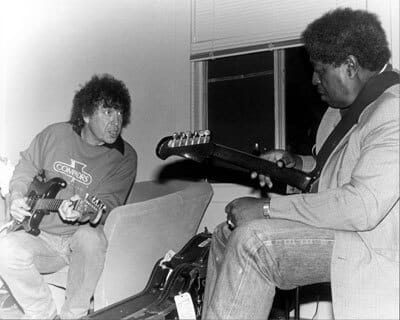

ElvinBishop.com

Southern blues artists migrate to Chicago

McDowell was a bluesman who never moved away from the Delta. But numerous Southern musicians relocated to Chicago and helped create a new, amplified blues style. They included Earl Hooker, Buddy and Phil Guy, B.B. King, Luther Alison, Big Walter Horton, Matt “Guitar” Murphy, Freddie King, Eddie Boyd, Lonnie Brooks, James Cotton, Eddie “The Chief” Clearwater, Jimmy Dawkins, Willie Dixon, Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James, and Sonny Boy Williamson I and II.

Sammy Lawhorn was a guitarist who moved up from Arkansas.

“Sammy Lawhorn was playing with Junior Wells,” Bishop said, “and he called me one day and said, ‘Man I want you to play with Junior for a week over at the Blue Flame.’

It was a better paying gig, so Bishop left J.T. Brown to play with Junior Wells.

“(Brown) was a little pissed when I walked over to the Blue Flame that night. I said, ‘You’re paying me $10 and he’s going to play me $12.’

“I walked over to Junior and said, ‘Hello, I’m Bishop. Sammy sent me over to play with you. He looked at me and said, ‘He did?’ He didn’t know anything about it. He takes me in the back of the runs me over a couple of tunes you could see I kind of halfway knew them. I suppose he thought at that point he couldn’t do no better anyway, so I played with him for a week in 1962.”

Theresa’s was another popular club. Theresa had a gun behind the cash register.

“I think everybody that that had a blues bar had a gun and you had to you know. I’ve seen people get shot in those clubs, and cut, too. And in a way it was good because it was better than it is now because it was before Chicago took on that hard, bitter edge, you know the drugs and the gangs and everything. Gangs were just barely starting up then and you wouldn’t see any hard drugs. That was more so associated with jazz guys.”

Phone-booth scuffle: ‘He cut him in the ass’

Lawhorn was among the people Bishop saw get cut. It was at Theresa’s.

“(Junior Wells was) a real sweet guy but he drank and he had a temper,” Bishop said. “We didn’t have cell phones; they had phone booths, you know. There was a phone booth inside the club that had one of those folding doors.

“I used to hang out with Sammy Lawhorn, a guitar player. Well, we went down there and he was in the phone booth making a call and somehow (he and Wells) got in a big argument and they’ve done that tussle inside the phone booth.

“And you know there’s not much room in there, so Junior got his knife out and all he could reach was Sam’s butt. He cut him in the ass. Sam comes out with the blood running down his pants. He said, ‘Come on man, you’ve got to take me back to my house to get my gun.’ So we rolled him around until he cooled down.”

Later, Bishop played with Hound Dog Taylor.

“I was just barely treading water trying to keep up with that gig because he would get us over for rehearsals at his house. And he would sit up there and we’d eat chicken wings and he sent me out with two dollars for a three-dollar bottle of whiskey. I’d get it for him, bring it back and everybody would have a few pops and we’d just play any stuff, none of which ever appeared on that gig.

“I remember him sitting in this chair. He had these long legs and his knees would be sticking way up over his lap and he’d be playing ‘Meet Me at the Bottom.’ And his pants were coming up way past his socks. And that was his idea of showmanship. He just sat up there and was himself. That was about it.”

Bishop said there were different crowds at the myriad venues.

“You’d have your circular clubs and they might include eight or 10 of them. There’d be a lot of people that you would never see, both artists and blues fans because their circuit would be different. I never hardly ever saw (Charlie) Musselwhite and he was there the whole time I was.”

Promoter Bill Graham see the blues light

Bishop went on to join the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, an integrated band that was approachable to white audiences. Bishop and Mike Bloomfield shared electric guitar roles — and mainstream America learned about blues music.

In the late 1960s, blues artists set out on another migration. The is one to ended in Northern California and included Bishop, Bloomfield, Musselwhite, Cotton, Luther Tucker and Magic Sam.

“Everybody said, ‘Boy this is cool. We don’t have to watch your back so bad like we do in Chicago. And we don’t have that old Hawk, that’s what they call that winter wind. And there’s lots of good-paying gigs. Gigs around Chicago tended to be pretty low level, financially. The weather was nice girls were friendly. There was just was nothing to not like about it.

“(Promoter) Bill Graham was the first guy who saw the possibility of opening up the music scene, doing what you might call mixed bills. He’d have Albert King, Ravi Shankar (Indian music) and Charles Lloyd (jazz) on the same bill. Before that, they were all separate different genres of music. Blues, up until him, was limited to ghetto clubs.

“It was part of the hippie revolution. So, within a year there was one of those big hippie ballrooms in every major city in the country.”

Elvin Bishop, 79, never left California. He now lives in Marin County. Since leaving Chicago, he has released 21 studio albums. His country persona, with his Southern drawl and bib overalls — and a penchant for an occasional gospel tune — led to his music at one point to be considered in the genre of Southern rock. That’s when he sold the most records. But ever since the early 1980s, he’s been considered a bluesman, a national treasure who honed his skills during the zenith of Chicago’s blues music scene. Stew over that.

— Tim Parsons

Related story: Concert review – Blues rolls on with Marcia Ball, Roy Rogers

Related story: Elvin Bishop talks about his Big Fun Trio.

- Elvin Bishop’s Big Fun Trio

Special guest: Curtis Salgado

When: 8 p.m. Saturday, Oct. 15; doors open at 7

Where: Crystal Bay Casino

Tickets: $40 (seated show)

3 Responses

Hey Tim: Great phoner with Elvin! When did you do the interview? Also, I had forgotten about the backstage interview with him and Billy Boy Arnold, but noticed the wall covering from dressing room #1 backstage at the SSR! Those were some great shows. In all the years doing entertainment, I enjoyed the blues folks above all other entertainers. To a man (and woman) they were all down to earth, friendly and absolutely void of pretension. Thanks for all you do to help keep the blues alive and well. Best. John…..

Tim; great article! Elvin made his deal with Alligator Records sitting on a bench in the very back of my club, The Odyssey Room (1969-1989), in about 1985 ? I’ll have to check that date ! Elvin played the Odyssey several times a year forever ! Elvin had called me up and asked if I could book him a particular weekend as the owner of Alligator Records wanted to come out and see him live ! I was happy and honored to do it and that Elvin had picked my club ! The gig happened and Elvin made his deal that night sitting on a bench in the back right out with all the patrons. Just a little bit of Rock n Roll (Blues) history for you !

Gary Schmidt

Newport Pop Festival

The Odyssey Room

The Reindeer Lodge

That is a great piece of history, Gary. Thank you for sharing it.