Chris Monaghan/ Alligator Records

Released today, “Alligator Records—50 Years Of Genuine Houserockin’ Music” — is a two LP/three CD compilation from the label started by Bruce Iglauer, who was inspired by blues when he saw Mississippi Fred McDowell play at his college campus. He started the label out of his Chicago apartment, making his first record by Hound Dog Taylor and the Houserockers in 1971. There’s been several hundred since, featuring legendary, influential artists such at Albert Collins, Koko Taylor and Lonnie Brooks to contemporaries including Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, Curtis Salgado and Rick Estrin & The Nightcats.

Amiable, accessible and at times loquacious, Iglauer spoke about his half-century at Alligator Records with Tahoe Onstage, a blues-centric website in the Sierra Nevada.

What a dauting task it must have been to pick the songs for this compilation. You had thousands to choose from.

It’s like choosing your favorite children. What I left out were hard choices. I would have been much happier doing maybe six CDs.

Assembling was hard but a lot of fun. I got to go back and listen to some records that I wouldn’t say were forgotten but were in the deep recesses of my brain cells. It was very nice to listen to records especially from the ‘80s and ‘90s that were done so long ago that they became fresh to me again. It was like a new listening experience.

Can you give me some examples?

Michael Hill’s Blues Mob, which I always thought was a very underrated band. And going back to the two albums we did with Billy Boy Arnold, especially the one we did with Bob Margonlin’s band, the “Eldorado Cadillac” album.

Nicole Fanelli / Alligator Records

I’ve seen the Paladins out here on the West Coast. I didn’t realize they were on Alligator for a while.

They play with so much passion. I always say the first thing I listen for is passion. I am not enamored with artists who hold back. Alligator is not a label of cool artists. Alligator is a label of hot artists.

Roy Buchanan is often mentioned by guitarists as a genius, and a tortured one at that. He didn’t sing on a lot of his songs. How was your relationship with him?

He started on lap steel, country music. That’s where he gets the incredibly big string bends. … Roy was such a sensitive guy. He got hurt very easily. … He was always easy to get along with. He brought cigars to studio for me.

When we made “Dancing on the Edge,” I realized we needed one more slow blues. … (I suggested) “Drowning on Dry Land.” After he listened to it, he said, ‘That’s the story of my life.’ He’s never heard the song before and he cut it the same day. That was a live vocal because he felt the song so much. And he just emersed himself in it. It tells you a lot about Roy and how deep his emotions were.”

Steve Kagan / Alligator Records

So many Alligator artists have died. It must be very hard to deal with that.

What I hate most is when somebody dies and I think they have more room to grow as an artist. That they haven’t yet recorded their best work. Michael Burks would be the first example that came to mind.

I’ve been to a lot of funerals. Luther Allison being another one. He was at the peak of his career when he died. And Roy, I can’t say he would have made better records but he was prepared to make records as good as the three he did for us. And then I think about Katie Webster, who I loved working with. She was felled by a stroke. She continued to perform but wasn’t as good and eventually deteriorated.

Paul Natkin / Alligator Records

You are known for being close with the musicians.

How could you love the music that people create and not love the artist who created it? For artists who have been with other labels, I think that they are amazed at all the personal attention they get, not only from me but the whole staff. I remember after we signed Marcia Ball, she said he’d heard from us more in the first six months than she did from her previous label in 20 years. A number of times people have been guests in my home. Everybody has my cell number. They know that I’m there for them and the staff is there for them.

Your newest artist, Chris Cain, told me he was thrilled to be signed and that the Alligator staff feels like family.

One of the things I’ve really done right is hiring. I’ve been able — some by dumb luck and some by instinct — to assemble a group of people who are absolutely reliable, who are dedicated to their jobs. They are not just working for the money of because it’s their profession. They are working because they are on a mission, just like I am.

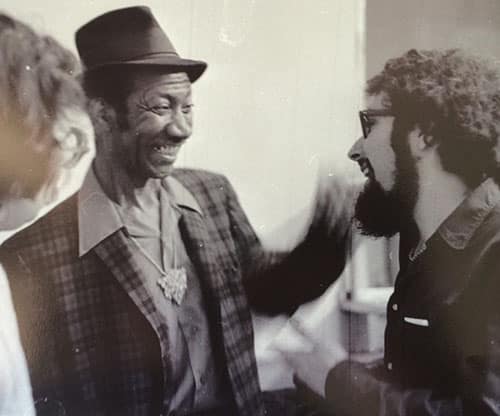

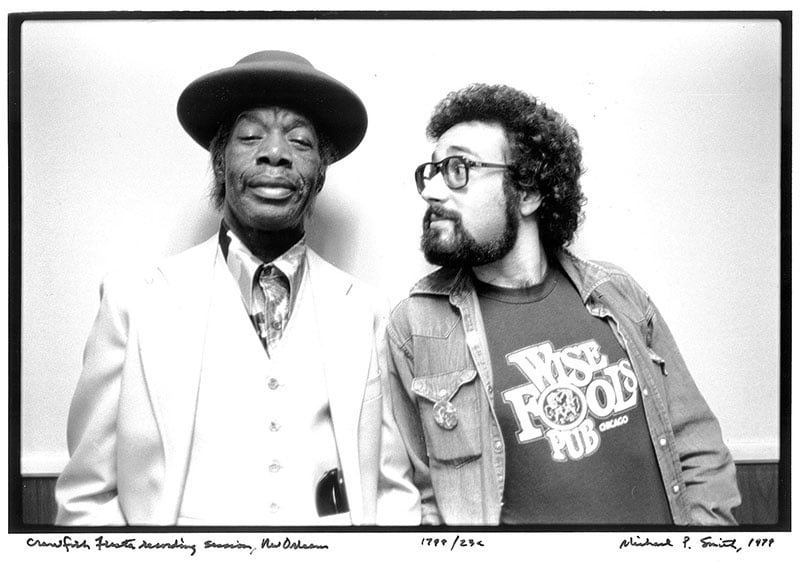

Professor Longhair made one album with Alligator and I was surprised to learn the guitar player was Dr. John, the piano great. The solo on “It’s My Fault, Darling” is wild.

Guitar was Dr. John’s first instrument. He had part of one of his fingers cut off. So he switched to piano, which would seem counterintuitive. I found it interesting in listening to that solo again. It kind of reminded me of the solo “The Things That I Used to Do” by Guitar Slim who recorded that song in New Orleans and that would have been all over the radio when Dr. John was growing up. It was interesting it was such an old-school solo.

He didn’t want to solo I had to talk him into it. He was happy to play rhythm guitar the whole time. He opened up the guitar case and not only was it covered in dust, but the strings were rusty it had been so long since he’d played. But it came right back to him.

Paul Natkin / Alligator Records

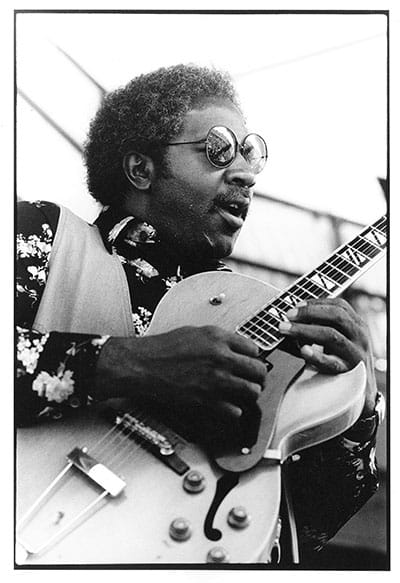

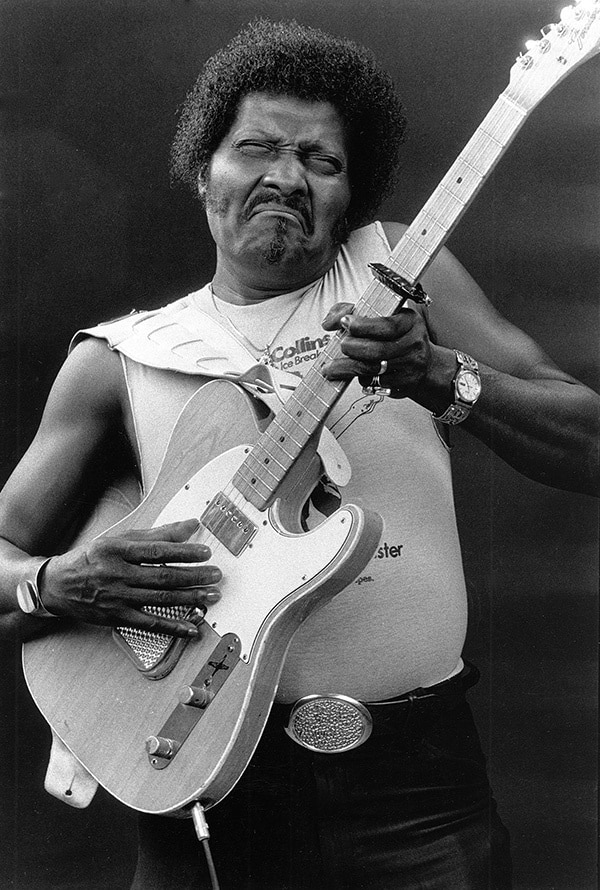

In your book, “Bitten By The Blues,” you wrote Alligator came to national prominence after it signed Albert Collins.

I never thought Alligator would be big enough to sign an artist as famous as Albert Collins. When I was first learning about blues guitar, I knew there were three guys named King and a guy named Albert Collins. At that point we had 15 records. We were tiny. We were operating at that point out of my house and warehousing in the basement. For me to sign Albert Collins was just unbelievable. I was terrified because he wanted $1,000 in advance. Of course, “Ice Picking” went on to be one of the most successful records at Alligator and made many, many times that. And, of course, Albert got his royalties. But the thought about being scared about $1,000 to get Albert Collins now seems hilarious.

The first flier the first album you made 50 years ago, “Genuine Houserockin’ Music,” for Hound Dog Taylor and the Houserockers certainly has endured.

I didn’t think of it as a tagline or slogan when I first put it on the very first promotional flier for the record. It read well and I began thinking about the meanings of the words: Genuine because the music is all rooted in tradition. House because its ultimately intimate, the musicians carry themselves as if they are in your living room, not like in an arena. The rocking part is that it will not only rock your body but also rock your soul. It will have that deep impact of healing feeling that the blues gives you.

Mike White / Alligator Records

What is the future of the label and the blues? You have young artists such as Selwyn Birchwood and Christone “Kingfish” Ingram who can carry the torch.

Part of my mission is to find and develop the people who are going to move this music forward over the next 50 years. I am always looking for talent like Kingfish and Selwyn who can grow musically and artistically and haven’t peaked and who make the music relevant to a younger audience. I want to make sure if somebody whose 18 or 19 hears this music that at least rhythmically and lyrically it will give them something that they can relate to. I talk to artists all the time about writing contemporary stories. No picking cotton, no mules. Love and loss is fine — that’s universal –, but if you are going to used metaphors, use up-to-the-minute metaphors.

And Selwyn, Toronzo Cannon and Shemekia Copeland have made strong social statements. Blues is not a music that historically speaks out about social issues. Blues is more personal and if you sing about social issues someone might lynch you. I am liking that these artists are confronting what’s going on in the world now. I would like to find more artists who are writing with that attitude. So for me having Kingfish and Selwyn is not sufficient. I need to have five or 10 more artists on my roster who can grow and be artists that will be popular and be relevant 50 years from now. As I am in my 70s that’s central to the mission of what I want to do with the label in the next few years, develop younger talent.

-Interview by Tim Parsons

Related stories:

Album review: “Alligator Records—50 Years Of Genuine Houserockin’ Music,” Tom Clarke writes, “This is the most entertaining modern blues compilation I’ve ever heard, and I’ve heard many. LINK

Book review: “Bitten by the Blues, The Alligator Records Story,” Tim Parsons writes, “Alligator’s history is meticulously documented, but described concisely and with an entertaining flare. It’s the kind of book a reader doesn’t want to end. And it doesn’t, really, because it can be used to reference esoteric music industry milestones and many visionary artists. LINK