Kenny Davis Jr.’s turnbuckle of life occurred the day his son was born.

Turnbuckles connect ropes to posts in corners of a boxing ring. Two threaded eyebolts adjust the tension of the ropes. With the birth of his first child, the 24-year-old boxer made the supreme connection and decided to use it to turn a corner.

“I was going down the wrong path,” he said. “I was hanging with the wrong crowd. Not making the best decisions. I kind of lost myself.”

Was it gangs? Drugs? Booze?

“All of the above,” the boxer’s father said.

Ken Davis Sr., who trains his son, is a barrel-chested, weight-lifting fanatic who can bench press 400 pounds five times. A former amateur boxer, the elder Davis, 44, used to take his son to the gym during his workouts.

“Kenny wanted to box, but he was only 4 or 5 years old — too young. “So I put him in Kenpo (a Japanese martial art). He had 21 fights until he was ready to come box. When he was 8, he started boxing and that’s when I stopped.”

“Kenny is a very talented and gifted athlete. He did everything. But as he got older … he chose to concentrate on boxing and football.”

Kenny Davis Jr. was a running back and cornerback at Reno’s Wooster High School, named by his coaches as most valuable player three seasons.

With a penchant for slipping punches and landing counter shots, he won two national Junior Golden Glove championships and was runner-up two more times, as well as advancing Silver Glove nationals and the 2011 Junior Olympics. He accepted an athletic scholarship to box for Olivet College, a Division 3 school in Michigan. He won the USIBA national title. He had a 78-13 record amateur record.

Tim Parsons / Tahoe Onstage photos

Trouble in Reno

The trouble began when he returned home to Reno. It became so dangerous for Davis Jr. that his father sent him away to escape gang life.

“Watching him self-destruct broke my heart,” Davis Sr. said.

To prepare for professional boxing, Davis Jr. worked for eight weeks in Pennsylvania under the tutelage of veteran trainer Buzz Garnic, who improved the prospect’s footwork and nutritional knowledge.

For his pro debut, Kenny was scheduled to fight at 130 pounds. But two weeks before the bout, the opponent pulled out. A fight in the 135 pound category was agreed upon. Then two days before the fight, that opponent pulled out. Davis wound up facing 143-pound Kevin Shacks.

“That guy was huge,” Davis Sr. said. “But the worst thing about sending him to pro camp would be to not have him get a fight.”

Despite the size disadvantage, Davis Jr. fought to a four-round draw in April 2017.

Adversity continued outside of the ring. And inside it, Davis Jr. lost a pair of decisions, dropping his pro record to 0-2-1.

“I hurt them both but didn’t have enough in the tank to finish them off,” Davis Jr. said. “I didn’t train one day in the gym for those fights. Lesson learned. I’ve got to prepare. It doesn’t matter how good I am or how good I think I am. Fights are won in preparation.”

Davis Jr. finally began to train in earnest last fall when opportunity rang. Roy Jones Jr. Promotions put him on an Oct. 25 fight card at the Silver Legacy.

“Boxing was really far from my mind and then I got a call,” he said. “Growing up my whole amateur career I always watched Roy Jones Jr. tapes. I tried to incorporate some of his moves into my style. It was a very good opportunity for me to fight in my hometown. What better way to kickstart my comeback?

“We had three-weeks notice. I looked at dad and said, ‘We’ve got enough time. We know what we’ve got to do to get in fighting shape.’ We did the most we could in those three weeks. I was walking around at 157 and I got down to 140 for the fight.”

First pro victory

Davis Jr.’s superior hand and foot speed led to his first pro victory, a four-round decision in the super lightweight division over Stockton’s Phillip Schwartz, who had a four-inch height advantage.

Five weeks later, on Dec. 1, the turnbuckle moment arrived in the form of Kenneth Davis III, who was born with a nickname: “K.D.3.”

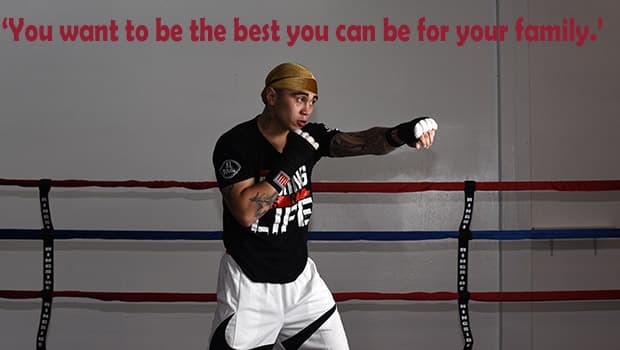

“It’s a newfound motivation for me,” the young father said. “You want to be the best version of yourself. You want to strive and be the best you can be for your family.”

His father witnessed his son’s metamorphosis.

“It looks like he’s turned it around for good,” he said. “He’s walking with pride. He’s speaking clearly. All those cobwebs he created in his head are gone.”

Davis’ training camp is called Team Supreme. Its stable includes Davis, super lightweight Peter Cortez, who has a 2-1 pro record, and Arhan Castillo, a 6-foot-4, 306 pound heavyweight prospect who is about to turn pro. Davis Sr. is the coach and he stresses weight training to improve explosiveness.

Boxing’s paradigm consists of championship fights and the matches that lead to those title fights. In the latter, there are the boxers who are expected to win and then there are the opponents. By starting out with a two loses and a draw, Davis for now is in the opponent category.

The strategy for Davis is to stay in fighting condition, train with Team Supreme and to be selective about which offers to take, and then deliver an upset win. The good news is that opponents are a sought-after commodity.

On Feb. 29, Davis Jr. traveled to San Mateo for face Derick Barthlemay, who has a losing record but three times as many pro fights as does Davis, plus an undefeated record in MMA.

“I was sharpshooting and my movement was really good,” Davis Jr. said.

However, the more experienced Barthlemay backed him into the ropes in the second round.

“I was blocking the shots with my arms, and as soon as he threw the right hand I saw the opportunity to throw the left hook.”

Davis Jr. connected a left-right-left combination, buckling his foe’s knees. Going for a knockout, he boxed furiously for the remainder of the round.

“That kind of took the wind out of me. In the third round he stepped up the pressure on me and made me dig deep.”

Davis scored a decision victory to even his pro record at 2-2-1.

Top of the world

Davis and Team Supreme stablemate Cortez are on a fight card scheduled for May 1. However, the coronavirus situation might postpone the event. Nevertheless, the future has never been brighter for Davis Jr. and his family.

“I am very blessed where I am right now,” he said. “Everything’s balanced out. I’m happy. I am where I need to be for my family. Everything is wonderful right now. I am feeling on top of the world.”

Ken Davis Sr. said, “It never crossed my mind to give up on him. It was heart wrenching to see his talent just being wasted, just self-destruct for 3 1/2, 4 years. He dug himself a hole and he was lucky he was able to pull himself out of it. To see him make a complete 180 turn makes me the proudest dad I can be.”

Boxers, even more than blues musicians, are supposed to have nicknames. Davis Sr. has a special appreciation for the classic fighters and he came up with “Hurricane” for his son, in honor of the fierce middleweight Rubin “Hurricane” Carter.

“It had a ring to it when they announced me for the last fight, ‘Hurricane Kenny Davis.’ But I’m still debating (a nickname) because something inside me says I’ve got to earn it.”

Perhaps someday we’ll hear: “And in this corner, it’s ‘The Turnbuckle’ Kenny Davis.”

— Tim Parsons

- The artist rendering at the top of the story was created by Edwin Nutting of El Cajon, California, who says, “I have been illustrating ideas since 1978. The truest art is a combination of minds, conversations started. View his work at Nuttingairbrushgallery.com — Instagram: Nutting , Nutink

——————————————————————————–

Michael Smyth / Tahoe Onstage

Shaun Astor / Tahoe Onstage

One Response

Great Job on The Article!!The Kenny Davis and Supreme Team.